By Brian Kahn

November 14, 2016

Some of the best years of my life were spent on the side of a volcano near the southern end of the Cascades in Oregon working for the National Park Service as a ranger.

When I put on the Smokey the Bear hat at Crater Lake National Park, I had to be an expert (or at least give off the air of one) on everything from geology to wildflowers to cultural history to the all-important locations of the bathrooms. I answered a lot of questions and frequently posed some back for visitors. But there was one topic I always felt leery to broach.

Climate change was on my radar but a growing divide around it made it feel off limits, especially in the setting of the national park system, where more than 300 million Americans annually escape to fish, hunt, ski, swim, hike, camp and cook out. Plus, what visitor wants their s’mores ruined by the reality that the splendor of the park they’re visiting could totally change thanks, in part, to the emissions from the very RV that brought them there?

In hindsight, it was silly and baseless to feel that way, but I wasn’t alone. It was a view shared by many rangers, not just at Crater Lake, but across the National Park Service. A 2012 survey of National Park and Fish and Wildlife Services staff grossly underestimated how concerned visitors were about climate change. Staff members thought that only 16 percent of visitors were somewhat, very or extremely concerned about climate change. In reality, that number was actually 83 percent.

Clearly there’s a huge chasm in perception, but it’s a gap the National Park Service has started to address in wholesale fashion.

Climate change is now a centerpiece of the National Park Service’s visitor outreach strategy (though that may change under president-elect Trump). In many ways there’s no better place to talk about it. Parks are wildly popular, and in those friendly settings, it’s easy to literally see some of the impacts climate change is having on iconic landscapes and endangered species.

A ranger-led hike in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. More rangers are engaging the pubilc in talking about climate change on hikes, in visitor centers and giving talks. Credit: National Park Service

One of the key things that brought climate change out of the shadows in national parks was a change at the top. Barack Obama’s presidency signaled a major shift in how the U.S. government approached climate change after 8 years of complacency under George W. Bush. And the National Park Service has been among the most proactive agencies in making climate change part of its mandate, in no small part because Jonathan Jarvis was appointed its director shortly after Obama took office.

“There were a few parks where people were taking on the topic 10-15 years ago,” said John Morris, a retired park ranger in Anchorage. “I have seen an evolution. The new director, Jonathan Jarvis, comes from science and has strongly supported (talking about) climate change. He and other managers have made it easier for rangers to grasp and address this topic.”

“In the previous presidential administration, we were not supposed to talk about climate change. It was not to be done,” said Brian Forist, a PhD student at the University of Indiana who studies climate communication in parks as well as a park ranger of 40 years. “A dramatic change happened in 2009 when the new president took office.”

During the Bush years, a series of high-profile incidents showed the administration had little interest in addressing climate change. That includes not ratifying the Kyoto Protocol — the predecessor to last year’s international Paris Agreement on climate — and pressuring scientists to downplay the importance of global warming.

The Obama administration has reversed course on a number of climate fronts. While the Paris Agreement and Clean Power Plan are high on the administration’s list of climate achievements, talking more about climate change in national parks is also right up there on that list. It’s one of the few federal agencies most Americans interact directly with year after year (well, except for the IRS, but that’s not exactly a beloved agency).

Beyond political will, park service staff have recently come to the realization that it’s not the first tough topic visitors have confronted on their summer vacations. In fact, people have been using their vacation days to visit places that tell dark and cautionary stories for decades.

“People aren’t afraid to talk about difficult issues on their vacation,” said Larry Perez, a communication specialist with the NPS Climate Change Response Program. “Look at Antietam National Battlefield, or Manzanar National Historic Site, which is the site of Japanese internment camps. We tackle critical issues all the time at national parks.

“Beyond parks, think what people spend their free time on. A show about the zombie apocalypse is the most popular thing on TV.”

(That show would be The Walking Dead in case you live under a rock).

Climate change might not exactly make for riveting television, but if there’s a way to get people’s attention about it, it’s seeing its impacts firsthand in parks. That leads to the second big realization that’s been happening across the whole system of parks, monuments and other sites: they’re living textbooks and the changes happening are clear as can be in many areas.

“The reality of climate change is facing us in national parks,” said Brian Ettling, a ranger at Crater Lake National Park in Oregon. “You can’t deny it or go around it so it’s important to engage visitors no matter what.”

Melting glaciers, disappearing beaches, changing growing seasons and more potent wildfires are all reshaping the landscapes millions of Americans hold dear. And because the park service has been entrusted to protect these places, it makes sense that rangers should be talking about the outside forces that are reshaping them.

Brian Ettling is one the rangers leading the charge to talk about climate change in parks. Credit: Brian Ettling

A Yale/George Mason University survey showed that 73 percent of respondents trusted the National Park Service as a source on climate change. That’s higher than the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy, mainstream news and even Barack Obama.

Of course, while climate change may be the central theme, not every message — or messenger — is the same.

Ettling gives an hour-long campfire talk throughout the summer that involves a rubber chicken, some clip art and electric cars.

“I try to use a lot of humor in my program,” Ettling said. “When people are laughing with you, it opens them up. Part of climate change communication is getting people more comfortable talking about because it is a heavy subject.”

In the case of Crater Lake, there’s a lot to know. The most obvious impacts have been a 37 percent decrease in snowpack since the 1930s compared to the 2010s and 1°F increase per decade in the lake’s surface temperature since 1965, both dates when monitoring began. Air temperatures have also risen about 1.3°F over the past 100 years.

Combined, these forces are creating a cascade of impacts across the park. Those include dying whitebark pine trees, more intense fires, less water for local communities, and the prospect that Crater Lake — the clearest lake in the world — could lose some of its clarity.

Ettling’s hour-long talk about climate change is a rarity (as is his use of a rubber chicken, which helped earn him an appearance on Comedy Central’s Tosh.0), but Perez said parks are still finding ways to fold it into the visitor experience.

And when Perez says “parks” as opposed to rangers, that’s exactly what he means. Not all of the 300 million visitors to the nation’s parks will have a chance to talk with a ranger or even want to for that matter. To address that gap, parks are trying to be creative with how and where they share information about climate change.

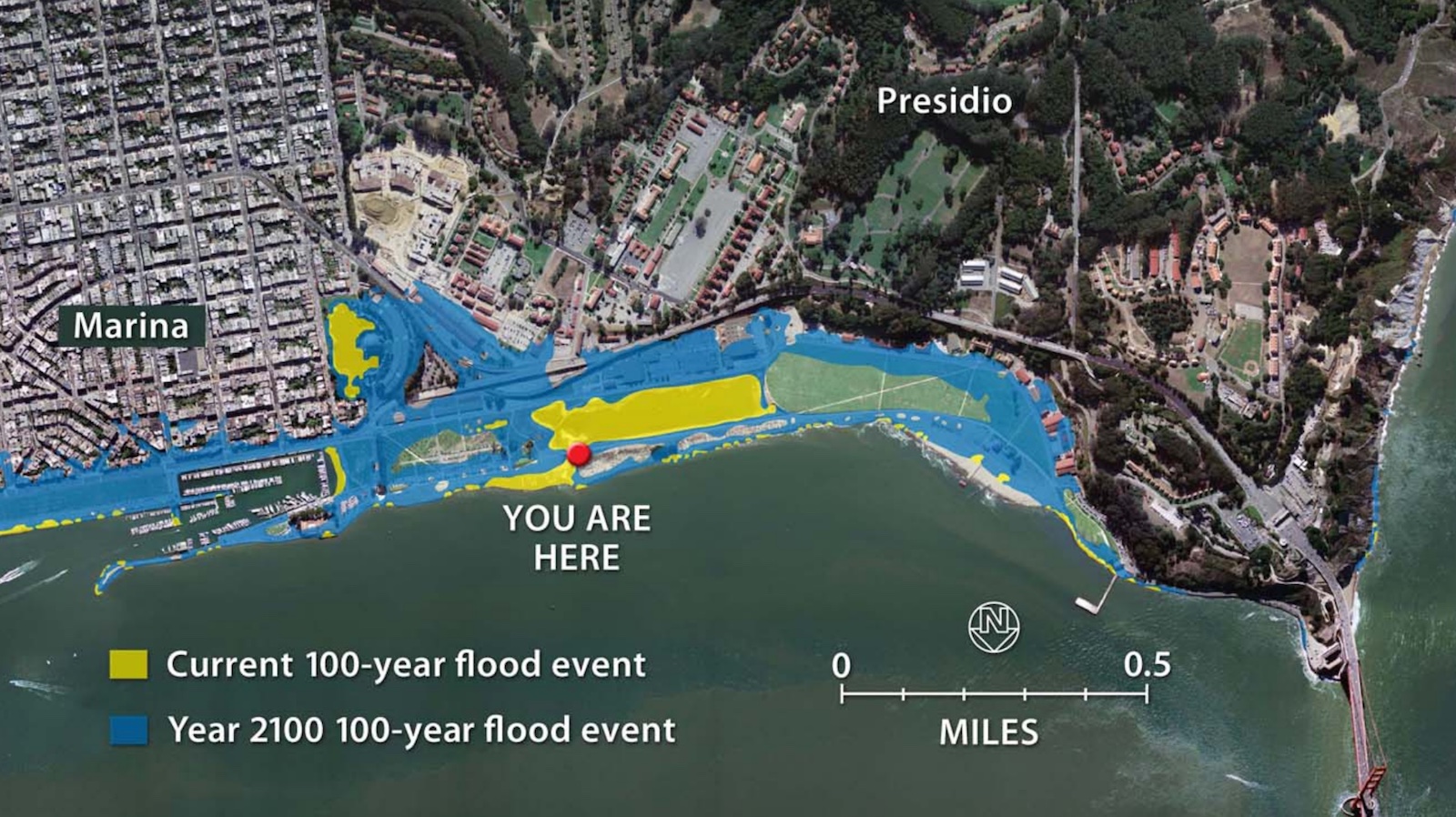

At Golden Gate National Recreation Area in the Bay Area, sea level rise is the biggest concern for the park’s beaches and infrastructure. To communicate the reality of what that means, the park installed metal poles with bright plastic balls attached that mark future sea level projections all the way out to 2300 as well as what storm surge could add to the tides. In case the pole wasn’t clear, there’s also an exhibit next to it explaining the different marks and why they’re there.

A section of the display at the Presidio talking about sea level rise impacts in the area. Credit: Golden Gate National Recreation Area

The Presidio, located on the northern edge of San Francisco, is among the area’s busiest spots so that’s exactly where the first batch of poles went up.

“One of the things about the outdoor exhibits is if we put them in places we know we have a lot of visitation, we know people will look at at them,” said Will Elder, a ranger at Golden Gate who spurred the pole project.

But parks’ secret weapon in conveying the realities of climate change might actually be something most visitors bring into parks with them. Smartphones and tablets are a huge part of how people experience the world today and some parks are thinking of how to leverage them to ensure what visitors experience and learn in the parks is just a swipe away.

Before he retired, John Morris helped write a climate change-oriented iBook visitors can get on their iPhone or iPad that covers impacts as well as actions that Alaska’s parks are taking. Morris said the goal is to get visitors to explore climate change in the parks and continue learning about it after they go home.

But that’s only the tip of the iceberg for what the parks could do with the smartphones and tablets that have become ubiquitous, even on the highest mountaintops or in the deepest canyons where cell phone reception is spotty at best.

“Pokemon Go demonstrates the power of location-based recreation, engaging people and telling place-based stories,” Perez said.

The National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, D.C. are already leveraging the game and having ranger-led Pokemon hunts to get visitors chatting about more than Magikarp. Using augmented reality to show visitors the impacts of sea level rise or glacier loss on their phone is one possible way that parks could leverage the tiny computers sitting in almost every visitors’ pocket or backpack.

And for those not able to get to a park, there are even more cutting-edge ideas to convey the impact of climate change on parks.

“You think of Oculus Rift and virtual reality, we’re going to be going down that route,” Perez said.

While virtual reality could well bring climate change (and parks for that matter) to a new audience, visitors seeing the stunning backdrops and cultural icons are still the National Park Service’s biggest asset when it comes to getting people to think about climate change.

“When I’m in a national park and I’m in uniform and I’ve got this fantastic park behind me, I have a huge home-field advantage,” Ettling said. “I feel like a pitcher with a 5-run lead in the first inning.”